Farming while Black:

How 1 mother is fighting to end racism in the food system

As a young mother, Leah Penniman was struggling to find fresh food for her children. Penniman, 39, and her husband, Jonah Vitale-Wolff, lived in the South End of Albany, New York, from 2005 to 2010, where there were very few options for fresh produce — only a corner store, a liquor store and a McDonald's.

Constantly in search of better things to eat, the couple ended up paying more than the cost of their rent on a CSA to provide vegetables for their young children, Emet and Neshima, now 14 and 16.

Equipped with masters degrees and over a decade of farming experience each, Penniman and Vitale-Wolff decided to establish a community garden near their home.

The couple’s personal endeavor to feed their family — and their community — soon birthed Soul Fire Farm, a BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of color)-centered community farm in Grafton, New York, that is dedicated to ending racism and injustice in the food system. Penniman, who is of Black Kreyol ancestry, is now determined to train the next generation of activist farmers, both locally and across the country.

Leah Penniman and her husband were spending more on fresh food for their children than they were on rent.

The government classifies neighborhoods with a lack of access to fresh food as "food deserts," but because a desert implies something is a natural phenomenon rather than a man-made occurrence, Penniman prefers the term "food apartheid."

"It comes out of a legacy of redlining and housing discrimination, of divestment from communities of color, and has resulted in a situation today where if you're white, you're four times as likely to have a supermarket on your block than if you're Black," she told TODAY Food. "The system where if you're black or indigenous, you're more likely to have diabetes, heart disease, and other diet-related illnesses, not 'cause you don't know how to eat, but because there is a scarcity of affordable, culturally appropriate quality food that's accessible."

Today, Black farmers make up less than 2% of all farmers in the U.S., which is down from a peak of 14% in 1910, even though Black Americans comprised 9-10% of the population at that time.

"This is not because Black folks don't want to farm," said Penniman. "This is because of a whole legacy of discrimination, of institutional racism."

In 1910, Black farmers made up 14% of America's farmers. Today, that figure is less than 2%.

In 2006, Penniman and Vitale-Wolff decided to look for some land outside of Albany and grow food for their community. They started by checking out listings in the area, knowing they wanted to be close to Albany.

In order to buy the land that would become Soul Fire and build their house, Penniman and Vitale-Wolff used money they'd saved and borrowed from friends and family.

"Jonah took the timbers of the land of this region, together with the clay from the earth, and the waste straw from agricultural byproducts and crafted it into this beautiful home where love literally exudes from the walls," she said.

Vitale-Wolff built this home on the Soul Fire land for his family to live in.

Vitale-Wolff built this home on the Soul Fire land for his family to live in.

The plot they eventually bought would blossom into the 80-acre operation run by the Soul Fire Farm team.

Just this year, people from 37 states and three countries came to the farm to take a week-long farm-training course, BIPOC FIRE (Black-Indigenous-People-of-Color Farming in Relationship with Earth). Soul Fire Farm now has over 10,000 alumni across all of its programs. In 2018, she came out with her first book, "Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land." And in April, she won a James Beard Foundation Leadership Award for her work facilitating food sovereignty programs.

Penniman's hard work has paid off today, but when she was younger, owning a farm was nothing more than a dream.

Over 10,000 people have completed Soul Fire Farm programs.

An outsider seeks sanctuary

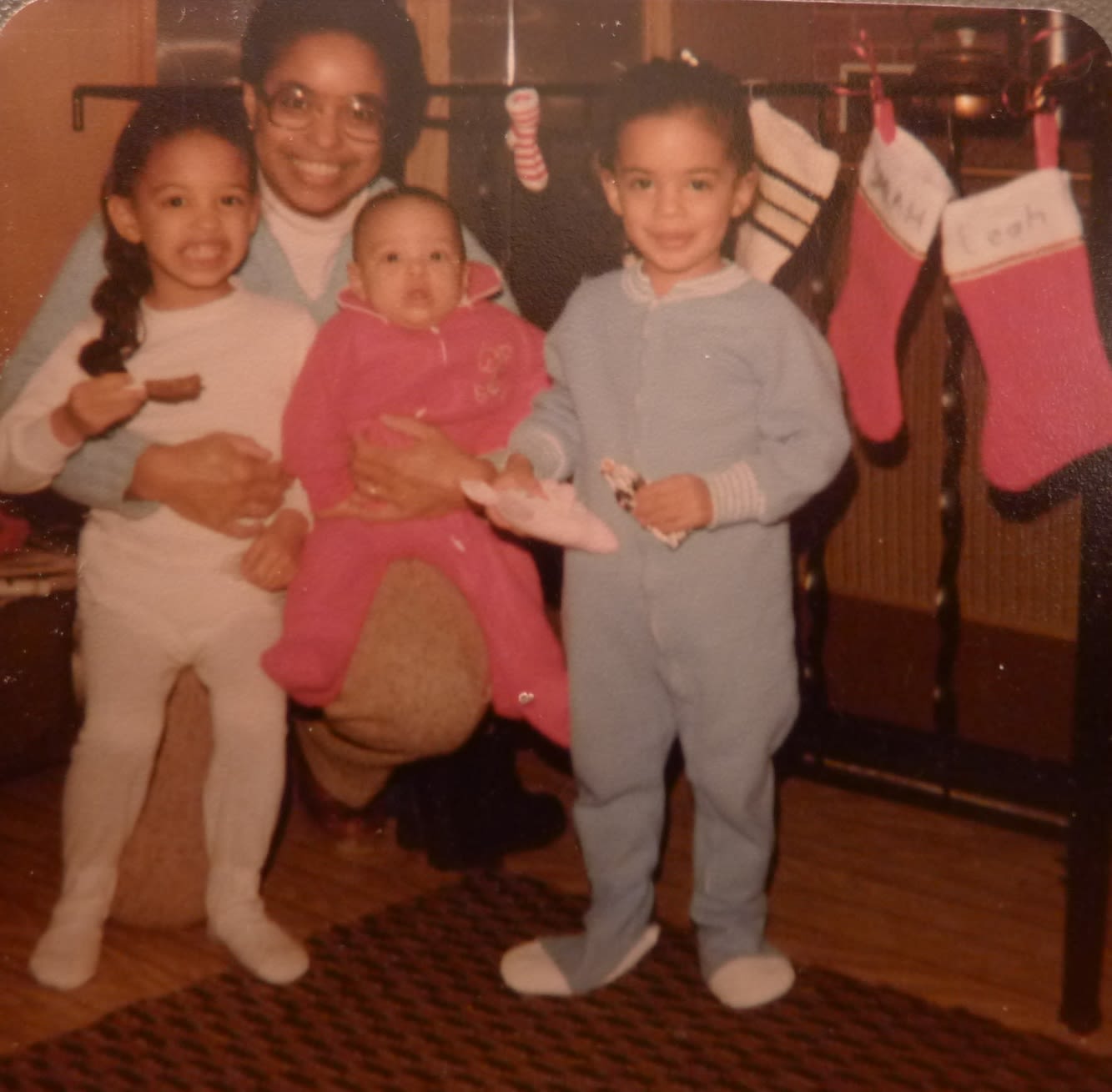

Penniman's love of the land has been a life-long passion. She grew up as the oldest of three in the small, rural town of Asburnham, Massachusetts. For most of their childhood, the Pennimans were the only Brown kids in their school — and they were bullied because of it.

From left to right: Leah, her mother, Adele, and siblings, Allen and Naima.

From left to right: Leah, her mother, Adele, and siblings, Allen and Naima.

"It ranged from taunting, you know, being called names to assumptions about our intelligence," said Penniman. "And it escalated in some cases to physical violence and assault."

She and her siblings would find solace in the forest. "I would literally go and hold onto grandmother pine and cry my tears and feel a sense of belonging and restoration from my connection with the land."

"I would literally go and hold onto grandmother pine and cry my tears and feel a sense of belonging and restoration from my connection with the land."

Her first few summer jobs were farming at rural and urban farms throughout Massachusetts. She attended every single farming conference she could afford to go to. But by her late teens and early 20s, Penniman started to wonder if she'd chosen the wrong movement, because she was surrounded by people who didn't look like her.

"I'd look around at these farming conferences and all the presenters were white," she said. "And I looked around and there was only a handful of people of color."

Leah's mentor, Karen Washington (left) and board member, Jalal Sabur (right), joins her at the James Beard Awards.

Leah's mentor, Karen Washington (left) and board member, Jalal Sabur (right), joins her at the James Beard Awards.

At one conference Penniman attended when she was 20 years old, she was fortunate enough to meet the woman who would end up becoming her mentor: Karen Washington, a political activist who specializes in the field of food justice.

Penniman recalls Washington telling her, "I know that, right now, it seems like you're out of place. But remember that our ancestors have been farmers for millennia and that our ancestors built the agricultural system of this country on their backs. And we're not gonna let them take it from us."

"Our ancestors built the agricultural system of this country on their backs. And we're not gonna let them take it from us."

- Karen Washington, political activist

Farming while Black: a history

Washington inspired Penniman to take a deeper dive into the history of how African Americans, Africans, Native Americans and other indigenous peoples contributed to modern farming. With every discovery Penniman drew more connected not only to her ancestors, but to her true calling.

There are innumerable ways in which modern-day sustainable agriculture (or permaculture) is rooted in Afro-Indigenous tradition. Composting can be traced back to Cleopatra, who recognized the important role earthworms played in fertilizing the Nile Valley. Penniman credits the Ovambo people of Namibia for the invention of raised beds, which can be seen at many organic vegetable farms today.

Farmworkers of the Ovambo tribe working field with hoes in Ovamboland, Namibia, Africa in 2005.

Farmworkers of the Ovambo tribe working field with hoes in Ovamboland, Namibia, Africa in 2005.

As early as the 1960s, Booker T. Whatley, PhD, of Tuskegee University in Alabama, saw that Black farmers weren't making money from wholesale farming and encouraged them to find people to be members of their farm and harvest their own produce. He called that operation "Pick Your Own" (or "U-Pick").

"People thought he was nuts at the time," said Penniman. "'Who's gonna come to a farm, do your harvesting for you, and pay you for it?' And he said, 'City folks who miss the country are gonna do that.'"

Booker T. Whatley (Mother Earth News)

Booker T. Whatley (Mother Earth News)

Many believe this was the start of the Community Supported Agriculture (or CSA) concept which continues to thrive throughout many metropolitan areas today.

Many people associate George Washington Carver, also of Tuskegee University, with peanuts, but they don't know why. His obsession with the popular nut stemmed from his love for regenerative and organic agriculture; the peanut is a legume and legumes have the ability to take nitrogen out of the air and put it back into the soil. In other words, peanuts restore degraded soils.

George Washington Carver's obsession with the peanut stemmed from his love for organic agriculture.

But since 1910, which was the peak of Black land ownership in the U.S., Black land ownership has decreased. This is, according to a landmark 2001 investigation by the Associated Press, due in part to the racial terror waged by the Ku Klux Klan driving Black farmers off their land. Their property was then folded into the deeds of white neighbors.

"A lotta times, we learn about the Great Migration as 6 million Black folks seeking opportunity in factories in the North," said Penniman. "But we don't learn about it for what it really was, which was a refugee crisis of people fleeing terrorism.

"And so, when I say that farming while Black is an act of defiance against white supremacy, it's really reclaiming our right to belong to the land in the face of all of these attempts to drive us off the land."

Of course, discrimination was also legalized. In 1982, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights reported that the federal government was one of the major causes of Black land loss. The commission concluded that the government would be responsible for the extinction of the Black farmer.

Since the Great Depression, through the Farm Credit Act, most farmers in the U.S. are entitled to things like loans, crop insurance and crop allotments, but Black farmers have had these programs systematically delayed or denied to them for generations.

"Farming while Black is an act of defiance against white supremacy."

Today, a major reason so little land is Black-owned is due to heir property loopholes. If a farmer doesn't leave a will, that land automatically goes to the children, then the grandchildren and so on, which means there can be many heirs for one piece of land. But the law also states that if just one of those heirs wants to sell, they can force a partition sale of the entire property.

"The practice began during Reconstruction, when many African Americans didn’t have access to the legal system, and it continued through the Jim Crow era, when Black communities were suspicious of white Southern courts," reports ProPublica. "In the United States today, 76% of African Americans do not have a will, more than twice the percentage of white Americans.

"So, right now, over half of Black land is in heir property," said Penniman. "And we're seeing a very rapid decline in Black land ownership because of the exploitation of these legal loopholes and forcing people off the land because some distant cousin on the West Coast wants to sell their share."

Black land ownership is declining rapidly because of the exploitation of legal loopholes.

Plus, Penniman said, some Black and Indigenous people stay away from farming because land is the literal and figurative scene of the crime as the setting where many lynchings, beatings and sharecropping took place.

"But the fact is, the land has always had our back. In fact, we survived because of that connection with the land." And if we run away from it, she said, "We leave behind the bones of our ancestors. We leave behind our stories."

In starting Soul Fire Farm, Penniman's goal was to reclaim the dignity of working on the land.

"The land has always had our back. In fact, we survived because of that connection with the land."

Training the next generation

Penniman's children have been involved in the project since the very beginning. "They both have gained a number of skills that I don't think they realize the full value of at their age," she said. "Neshima knows how to install a roof and edit a grant report, and Emet can facilitate a youth group and pack a CSA box."

Neither of Penniman's children aspire to be professional farmers (they say they both want to become engineers), but they do want to own large gardens and grow their own food, which certainly pleases their mother.

"We have a lot of teens that come through the farm, and not all of them are gonna be farmers," she said. "But I do think two things happen for every single young person who comes through. One is they see folks who look like them following their dreams and being their own bosses and running their own institutions. So ... whether they wanna open a restaurant or a hotel or a farm or be an engineer fundamentally doesn't matter to me."

"They see folks who look like them following their dreams and being their own bosses and running their own institutions."

Until 2016, when they started a nonprofit branch of the farm, the only help the family received was through volunteers or people paying out of pocket.

Now, Soul Fire has eight staff members who, in addition to managing the organization, the farm and its infrastructure, facilitate hands-on-the-land training (like BIPOC FIRE, their most popular course), as well as courses on business management, marketing, crop planning, anti-racism training, carpentry training and week-long camps for youth interested in farming.

Soul Fire Farm's employees are Cheryl Whilby, Larisa Jacobson, Lytisha Wyatt, Damaris Miller, Leah Penniman and Jonah Vitale-Wolff.

Soul Fire Farm's employees are Cheryl Whilby, Larisa Jacobson, Lytisha Wyatt, Damaris Miller, Leah Penniman and Jonah Vitale-Wolff.

"It's really whatever our community is asking us for, we do our best to provide," she said.

Penniman is also very committed to the accessibility of her programs, regardless of students' ability to pay. Every class fee is sliding scale based on what they earn, from zero on up.

Some people receive stipends to make up for lost wages because they're hourly workers who don't get days off for professional development at their day jobs. Penniman continues to raise funds to support this model through grants and institutional partnerships, as well as through paid public speaking appearances.

Soul Fire offers a week-long carpentry training called the BIPOC Builders Immersion.

Soul Fire offers a week-long carpentry training called the BIPOC Builders Immersion.

The farm also sells food. Almost 100% of Soul Fire's goods are distributed through a farm-share CSA model, with about 110 households within 25 miles of the farm. Patrons may pay using EBT benefits or whatever they can afford on a sliding scale, and then receive a colorful and nutrient-dense box of food, including vegetables, eggs, pastured meat and herbs, delivered to their doorstep on a weekly basis.

Every fall, at the conclusion of the CSA season, Soul Fire staff ask their members how the food has impacted their health, and the vast majority report improvements in their health — whether it's a reduction in blood pressure or cholesterol, or just an improved sense of well-being.

"Especially for our lower income members," said Penniman. "Many of them say if it wasn't for those vegetables, they'd literally be eating, you know, ramen and boiled pasta and canned foods because they simply don't have anywhere to get fresh food like we offer."

Almost 100% of Soul Fire's goods are distributed through a farm-share CSA model.

Almost 100% of Soul Fire's goods are distributed through a farm-share CSA model.

Sparking a movement

Today, many of Soul Fire Farm's BIPOC FIRE alumni are growing food for their own communities. And they don't just live in New York.

"There's nothing that makes me happier than seeing our alumni farm," she said.

Since 2013, Penniman has trained approximately 600 new BIPOC farmers and 86% of her graduates are actively growing food at a farm or community garden.

Outside of Atlanta, Georgia, Keisha Cameron (left) started a training program at High Hog Farm that was partly inspired by BIPOC FIRE to work with Black farmers in the region.

Outside of Atlanta, Georgia, Keisha Cameron (left) started a training program at High Hog Farm that was partly inspired by BIPOC FIRE to work with Black farmers in the region.

Penniman's work doesn't stop on the farm. She travels around the country, speaking at numerous conferences and universities, including Bioneers, BUGS, Harvard, Just Food and Yale.

"I've had mixed feelings in the past around doing public speaking," she said. "It always seemed like the real work was here on the farm, and then I'd go out and just talk about the real work. And something shifted for me when I witnessed how many people who heard our talks then went on to join a program to learn how to farm, or did something like give away their land to a Black farmer."

"Fundamentally, I want to create a different kind of educational environment for young people that I never got to experience."

Now, whether she's on the farm or at a podium, Penniman aims to create an educational environment where, she said, "you can be proud to be a soil nerd and have your culture uplifted, your heritage uplifted, be affirmed for who you are and encouraged to pursue your wildest dreams."

This deeply personal passion project began with her simply trying to feed her family, and it has grown into something that has touched the lives of thousands of people across the country — something she could have never imagined in her wildest dreams.

"My hope is that we spread our love, our knowledge, our resources out through the network of Black and brown farmers," she said, "so that, you know, ten, 20 years from now, people will be like, 'Wait, what's Soul Fire, again?' because there's literally right around the corner a Black- and Brown-led teaching farm and then the next state over there's five more, and so forth, so that it becomes so commonplace that we have to remind our children about a time when all the land was white-owned and a time when all the farmers were exploited because that's become such a distant memory."