Talking about race in an interracial relationship

More than half a century after interracial marriage was legalized, mixed-race couples still face unique hurdles. Here's what we can learn from them.

In April, when health officials urged everyone to wear masks in public in order to prevent spread of the new coronavirus, Bryan Williamson’s immediate thought was about how he, as a Black man, would be perceived while wearing one.

“The first thing out of Bryan’s mouth was, ‘I’m going to be seen as more suspicious,’” his wife, Catherine Williamson, who is white, said. “I never would have thought about that.”

When a neighbor made a batch of homemade masks for people on their block, they made sure to select the one with a bright floral print for Bryan. The couple, who live in Columbus, Ohio, and run an interior design company, have been married for over eight years. Yet Catherine is still learning about the considerations her husband must take simply because he is Black, the near-daily injustices that he refers to as “little paper cuts” — having to think twice before wearing a hoodie and sweats outside of the house or shrugging off someone who crosses the street to avoid him.

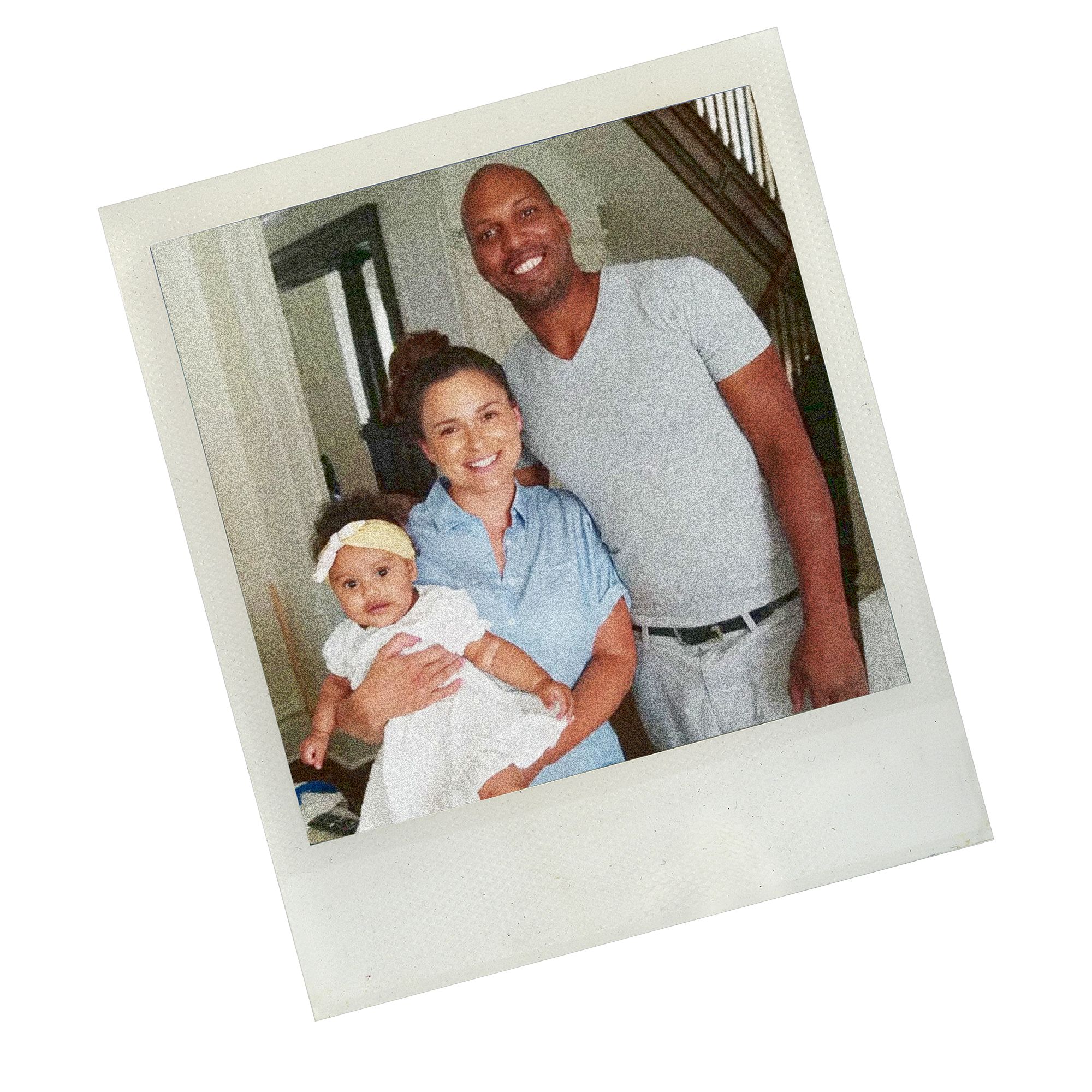

Catherine and Bryan Williamson with their daughter

Catherine and Bryan Williamson with their daughter

Of course, these aren’t new conversations for the couple, or for most interracial couples in which one person is Black. But over the past couple of weeks, as people across the country protested police brutality and marched in honor of George Floyd and others, many find the dialogue has intensified.

“I don’t know that we have ever talked about (racism) in this much depth and really gotten those thoughts out,” Bryan said.

The recent events have encouraged many to think more deeply about racism and white privilege, and the longtime mistreatment of Black people. Friday also marks the anniversary of Loving v. Virginia, the Supreme Court case from 1967 that overturned laws banning interracial marriages. The case involved Richard and Mildred Loving, a white man and Black woman whose marriage was initially deemed illegal according to Virginia state law. First married in 1958, it took the couple nearly a decade to win the right to legalize their union.

Marrying someone of a different race or ethnicity has since become more commonplace; in 2015, 17% of newlyweds in the U.S. had a spouse of a different race or ethnicity, according to the Pew Research Center. But interracial couples find there are still hurdles to overcome — especially right now. To commemorate that landmark decision, TODAY interviewed several interracial couples to learn about the discussions they’re having right now around race and racism.

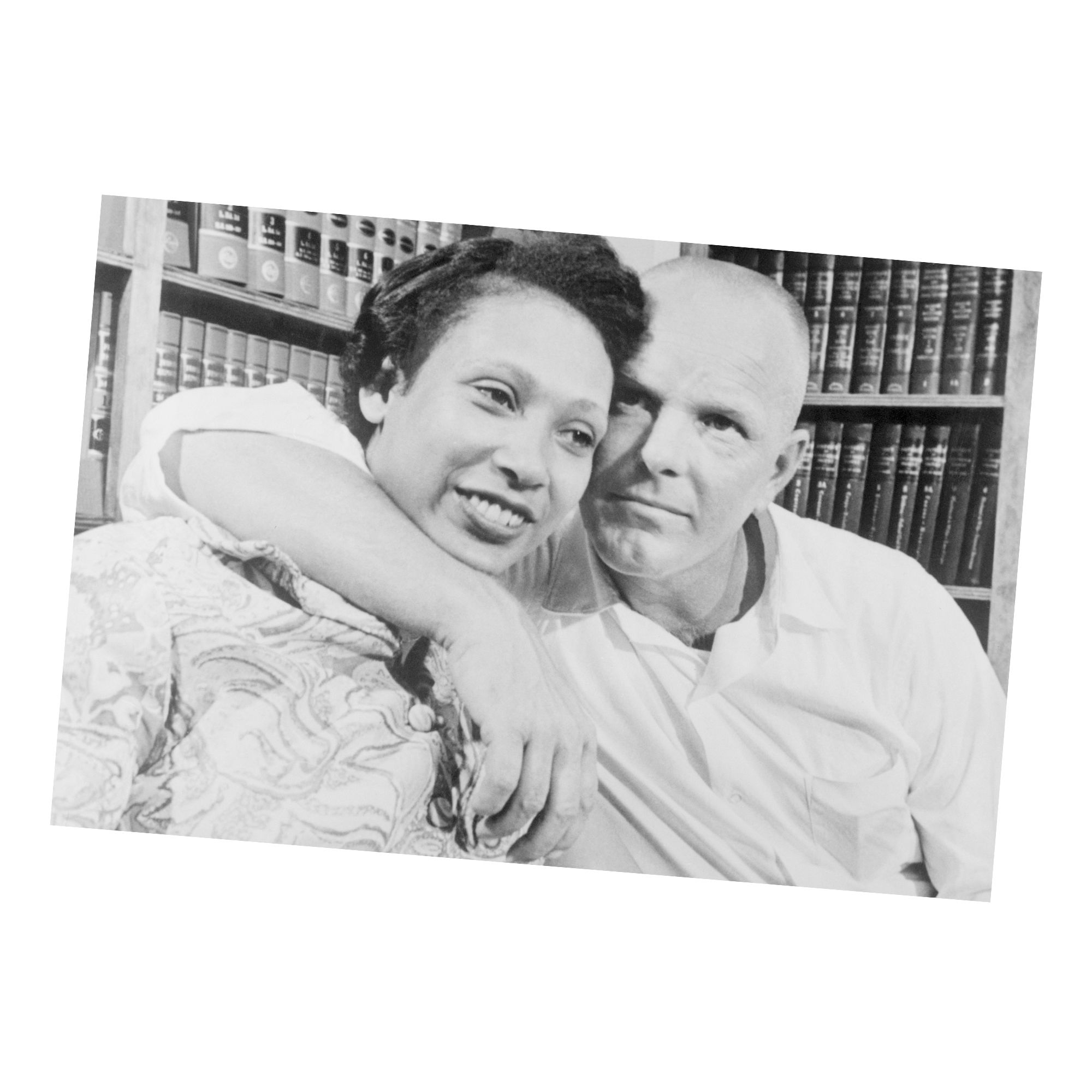

Mildred and Richard Loving. Their case overturned laws banning interracial marriages in the United States. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

Mildred and Richard Loving. Their case overturned laws banning interracial marriages in the United States. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

Jeena and Drue Wilder, from Dallas, Texas, recently got into an argument about whether white privilege exists.

“As a white male, my immediate reaction to someone saying white privilege is to take it negatively, as if any work I’ve done isn’t credited to me,” Drue said. His wife, who is Haitian, disagreed. Jeena Wilder has lived with racism her entire life. As a child, she remembers that when her grandmother had a stroke, her mother would not take her to the emergency room until they had all showered and dressed nicely, so that when they got to the hospital, the staff wouldn’t think they were seeking shelter or drugs.

“She told me, ‘You need to go put on your church clothes,’” Jeena said. “And I remember being so frustrated, because if she’s having a stroke, these are minutes we are wasting. And my mom said, ‘If she doesn’t look like a person worth saving, they are not going to save her.’”

Drue and Jeena Wilder with their four children

Drue and Jeena Wilder with their four children

Jeena, who runs a popular Instagram page about motherhood and adoption, said that she is so used to discrimination that she never even bothered to tell her husband about every little incident — until now.

“I really had to step back and reflect,” Drue said. “I’ve never gone to the ER or the hospital and thought about my appearance. If my mom was sick, we took her straight in. Put your slippers on, let’s go.”

Couples in interracial relationships have always faced unique obstacles, from disapproving friends or family members to cultural differences.

“I’m from a Jamaican background, so we do things (my wife) Julie has never done,” said Femi Redwood, a television reporter in Brooklyn, New York. “We wash chicken, we use bleach for everything — little things like that that sound crazy to Julie.”

Redwood said her wife’s family has been accepting of her and their relationship, although she has at times felt an “internal tension” at larger gatherings, such as weddings, where they didn’t necessarily know everyone.

“The fear wasn’t that someone was going to say the N-word or anything like that, but more the microaggressions, the coded language,” Redwood said, referring to subtle racism in the form of comments that often perpetuate racial stereotypes.

Femi Redwood and Julie Compton on their wedding day in 2018

Femi Redwood and Julie Compton on their wedding day in 2018

These concerns are commonplace for Black people in interracial relationships. But right now, they may be feeling additional strain, according to Chimere G. Holmes, a licensed professional counselor in Philadelphia.

“Intense emotions have sparked on a global level,” said Holmes, who herself is in an interracial marriage. “I’m finding that with a lot of couples, the person of color tends to feel very invalidated because their partner has not had the same lived experiences, and they may find it hard to relate.”

She urged couples to approach conversations from a place of “curiosity and calm.” But even in relationships where those conversations are happening, there will be missteps.

Redwood's wife, Julie Compton, recently realized she’d made a mistake when she asked her wife to watch a movie that included scenes of violence against Black people.

“I thought, in my naiveté, that because it was about race, she would be interested in watching it,” Compton, a freelance journalist, said. “It really upset her, and I could tell she was angry at me for having her watch the movie. It didn’t occur to me that it would bother her.”

Redwood was hurt by the imagery. “As Black people, sometimes you have to pull away from the Black trauma porn,” she said.

As tensions between communities and police continue to mount, many white people are just now getting a sense of the distrust of authority that many Black people have held for decades.

Cody Thompson, a Black man in New York City, said police stopped him multiple times recently when he was on his way to his overnight job as a doorman. It was the night before the city instituted a curfew, when looters rampaged several stores near the building where he works. His wife, Kristen Thompson, who is white, was on the phone with him the entire time.

“I could hear the police talking to him — asking him where he’s going, what he’s doing,” she said. “Every time he was stopped, my heart sank. I was crying my eyes out on mute, so he couldn’t hear me. I had never experienced anything like that before. I kept thinking, what if this is the last time I speak to him? I’ll never understand what it is like to fear for your life when you walk outside — I know my privilege in all of this — but going through that with Cody, I got just a glimpse into that feeling.”

Cody and Kristen Thompson

Cody and Kristen Thompson

Nicole Moore of St. Petersburg, Florida, said she has similar fears about what could happen to her biracial husband if he encounters police when she is not around.

“I worry that if I’m not there to try to de-escalate a situation or to back him up, I don’t know if he’ll walk back through the door,” she said.

Dallas and Nicole Moore with their children

Dallas and Nicole Moore with their children

In Snellville, Georgia, married couple Candice and Danielle Clark say the increased tension makes them nervous — doubly so because they are LGBTQ.

Plus, they've been targeted before. On their wedding night in 2017, they say a group of men physically attacked Candice, who is Black, after making a lewd remark to Danielle, at the hotel where their wedding party was staying. They called the police and the next day attempted to press charges, but the incident against Candice was not included in the police report, and the hotel had already deleted the surveillance video that would have shown the attack, they said.

"It was the first time we really had to sit back and see the world isn't all sunshine and rainbows," Candice said.

Candice and Danielle Clark

Candice and Danielle Clark

These conversations mirror the ones happening more broadly across America and on social media, where a largely white collective is struggling to understand the sweeping effects of systemic racism and the pervasiveness of police brutality. They might be able to learn something from the conversations interracial couples are having. Like, for example, that it won’t always be easy.

“There is always the fear in the back of your mind as a white person that you might say or do the wrong thing,” Compton said. “It’s easy to be subconsciously racist in ways you don’t realize when you don’t have somebody to call you out on it.”

And there will be mistakes.

“You’re going to say the wrong thing and that’s OK as long as you put your ego in check and listen,” Redwood said.

Holmes emphasized that, from a relationships perspective, it’s also important to know when to take a break.

“I’ve been telling my clients, you can’t fix these problems in one day. It’s OK to take a social media fast. You need to unplug sometimes. That’s a healthy boundary. Like, this is a night when we need to put race and the United States on the shelf and we need to watch Bravo and order takeout.”

“At the end of the day, we all know it’s much deeper than skin color in terms of why people love who they love,” she added. “This is really a clarion call to everyone to be willing to listen, to be curious, and to give it our all as compassionately as we can.”